It’s a story of economic failure, corporate consolidation, human pathos, and a struggle to find health care. It’s one of the quasi-legal billing practices and regular everyday people trying to do the right thing. This is not a TV soap opera, it’s real life, and it’s the story of the closing of rural hospitals across the United States. The closure of even one rural hospital causes hardship. There have been hundreds.

These small hospitals with 10 to 25 beds are often the economic center and communal heart of rural towns. When they close, they leave crevices of socio-economic hardship and gaping holes where there used to be access to healthcare. Tragically, the rate of rural hospital closures seems to be gaining speed. Although fault lines in the U.S. healthcare system are largely to blame for the closures, they place even more pressure back on the system. Telemedicine can jump in as a very effective solution to the growing problem of rural hospital closures and is doing so in many locales across the country.

Rural hospital closures, long-term pain

There are too many stories to tell here. There’s the 72-year-old woman in Woolwine, Virginia, who spends her days on a volunteer ambulance crew responding to calls ever since the local 25-bed hospital closed last year. There’s the board of directors of a 26-bed hospital in Cedarville, California, made up of local farmers and motel owners with no healthcare experience, who voted to let an outsider buy the rural hospital on the promise of reopening it. Then there are the headlines like “Soon-To-Be Mothers Hurry To Find Care After Rural Missouri Hospital Closes.” These stories may flash rapidly across the pages of media outlets. Still, they tell the story of long-term consequences for the people left in the wake of rural hospital closures – real people with real healthcare needs that are left dangerously unmet.

More than 120 of the 2,375 rural hospitals in the U.S. have closed since 2005, 83 of them since 2010. The Health Resources and Services Administration says rural hospitals “have been closing their doors more frequently and at higher rates than urban facilities in recent years — and a pattern of increasing financial distress suggests that more are likely to falter.”

A study published in Health Services Research determined that the closure of the sole hospital in any community has a definite economic impact:

- Reduces per-capita income by $703 or 4 percent

- Increases the unemployment rate by 1.6 percentage points

- It makes it more difficult to attract industry and employers

Other studies determined that a hospital closure creates:

- Decreased access to care for patients and an increase in travel time to care of 30 minutes.

- Barriers to receipt of crucial emergency services, including mental health and addiction treatment

- Increased need for emergency services

- Decreased physician supply

- Lack of access to specialists, including obstetrics

- Lack of access to diagnostic testing and laboratories

Sadly, the people affected by the loss of these small, rural hospitals tend to be minorities, the elderly living with chronic health conditions, and the poor. In other words, rural hospital closures impact those who can least afford to lose easy access to healthcare.

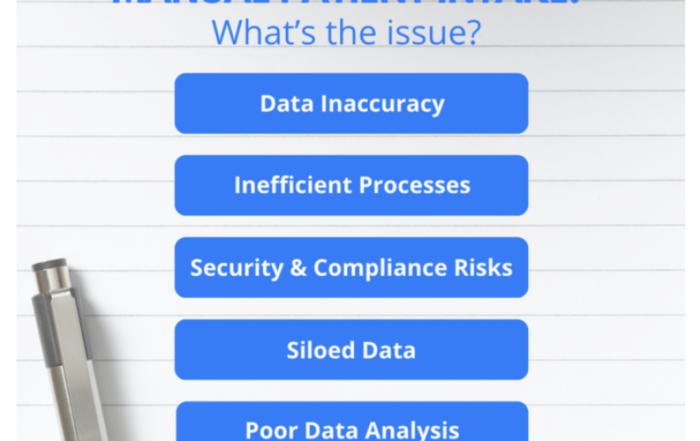

There are many reasons why small hospitals close. Factors include low patient volume, high rates of uninsured patients, older, sicker patients, and for-profit owners. Closures can be caused by market conditions, health system consolidations, reimbursement struggles, and dwindling cash flow. Whether or not the state in which the hospital is located expanded Medicaid can also be a factor and directly impact the level of reimbursements. Well-insured patients going elsewhere for their healthcare can reduce the patient volume to dangerously low levels. Large systems that own the hospitals may decide to close them based on financial and business decisions rather than assessing local needs. Though the reasons are many, the results are consistently troubling: “The closure of a rural county’s sole hospital decreases the economic well-being of the community and likely places the local economy in a downward cycle that may be very difficult to recover from.”

Carpetbaggers or saviors?

The story of Surprise Valley Community Hospital could be called a sordid tale – one of mismanagement, crushing debt, bankruptcy, and broken promises. Outsiders have filed in and out, promising money and management to keep the rural hospital open – none have panned out. Hospital executives practically resigned en masse when auditors showed up. According to news reports, federal regulators invoked a financial penalty. They suspended Medicare and Medicaid payments to the hospital over concerns about patient care.

Yet, the citizens want the small rural hospital to remain open, saying it would “take the heart” out of the community if it closed permanently. They tried to save their hospital by voting to let an out-of-town businessman buy the hospital based on his promises to save it. His premise was based on what can best be described as “quasi-legal” remote billing practices. Eighty-three percent of the voters that turned up for a special vote on the matter approved the sale of the hospital that is now $4 million in debt.

The out-of-town entrepreneur from Denver promised to turn around the hospital and make it profitable by billing for lab tests generated by telemedicine visits. He had never run a hospital before and did not show his financials to the hospital board before the matter went to the public vote. Some view lab tests generated for out-of-town patients as “a growing scheme.” His financial equation doesn’t seem to save the hospital quickly; 80 percent of the profits from his lab billings will go to this company, 20 percent to the hospital.

Unfortunately, this scenario is occurring time and time again at rural hospitals across the U.S. So-called “management companies” are swooping in with promises to save troubled hospitals, keep them open, and return them to solvency. We don’t like it when telemedicine or “telebilling” is hauled into the swamp. The technology holds too much promise and is too great a solution for healthcare to be sullied by quick-fix schemes.

Then there are the saviors. That 72-year-old woman we referred to earlier? She is Crystal Harris, an unpaid volunteer, and captain of the advanced life support squad of the Smith River Rescue Squad in Woolwine, Virginia. Last year, Pioneer Community Hospital of Patrick, a small 25-bed rural hospital near Stuart, filed for bankruptcy. When it closed, it put 100 people out of work and left about 19,000 people without an emergency room nearby. Now those people are served by 911 emergency response services.

Women expecting babies were left out in the cold with the unexpected closure of Twin Rivers Regional Medical Center in Kennett, Missouri. When that rural hospital closed, so did the only OB/GYN office in the area, which delivered more than 400 babies a year. Now, five physicians who are soon to lose their jobs at the hospital, the State of Missouri, and a hospital in a neighboring county are collaborating to maintain vital health care services in the area known as the Bootheel.

Physician shortages exacerbate the problem.

Even before rural hospitals began closing, there was a shortage of physicians in rural America. The National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) estimates that “only about 11 percent of the nation’s physicians work in rural areas, despite nearly 20 percent of Americans living there”. Statistics quoted by the NCSL illustrate the extent of the problem:

- Nearly 30 percent of rural primary care physicians are at, or nearing, retirement age

- Younger doctors under the age of 40 accounts for only 20 percent of the current workforce

- Advanced professional providers are already beginning to fill the gap: 41 percent of rural Medicare beneficiaries saw a physician assistant or nurse practitioner

- 17 percent saw them for all of their care

- 24 percent saw them for some of their care

- Demand for services will grow as physician supply shrinks: The rural population of those ages 55 to 75 is expected to grow 30 percent between 2010 and 2020

The NCSL concludes that “Thousands of additional primary care providers (PCPs) are needed to meet the current need in rural America and, over the coming decade, tens of thousands of additional PCPs will be needed to meet the growing rural (and aging) population. Consequently, many states continue to look at ways non-physician providers can play a larger role in providing primary care in rural areas.”

We would argue that the NCSL missed an important solution to the problem – telemedicine services. The United States cannot educate physicians fast enough to meet the looming shortage. Even if it does, rural areas often cannot meet the financial, housing, and professional demands of newly minted physicians. Therefore, they cannot draw them to work in those areas. However, when physicians can reach patients via telemedicine, access begins to improve. Instead of physicians and patients driving hundreds of miles to connect for healthcare delivery, it can be accomplished in a faster, more efficient manner through telemedicine. It facilitates chronic disease management and can improve post-acute care, even when a rural hospital closes.

Telemedicine fills gaps in care.

The rural populations left without access to care in the wake of rural hospital closures are often older, sicker, and poorer than urban populations. They live with more chronic conditions. Those who suffer from mental health issues and need addiction treatment require more frequent follow-ups and consistent communication with providers. Telemedicine does not shrink in the face of these needs; it rises to the occasion. It is the new delivery care model for many and perhaps especially rural populations.

Slowly, telemedicine programs are being implemented across the country to meet the demand left unserved when rural hospitals cease to exist. Farm and Dairy discussed one telemedicine program launched by Butler Health System in western Pennsylvania. The healthcare system established the telemedicine program for the rural agricultural community with a $137,755 grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) rural development branch. The hospital matched the funds from the USDA. The funds were used to buy telemedicine equipment and launch the program. Butler purchased mobile video carts, physician video units, educational carts, digital stethoscopes, and other medical instruments. Together, they create a program that allows the specialist and patient to see and talk to each other from different locations. Care is delivered face-to-face via telemedicine.

As a result, from day one, patients saved time and had increased access to healthcare providers. Physicians could see more patients more effectively. Butler determined the following:

- Patients saved more than two hours of drive time by seeing a cardiovascular specialist via telemedicine.

- Physicians said they could see patients living 100 miles away and inpatients without leaving the hospital.

- The hospital launched the service with electrophysiology and planned to expand into neurosurgery, endocrinology, and pulmonology telemedicine.

Telemedicine reaches out to improve chronic disease management

Chronic disease management can be improved exponentially through telemedicine. That’s because telemedicine directly reaches the home and across the miles to patients living in rural areas.

Case in point: MultiCare Health System in Tacoma, Washington. The system was an early adopter of telemedicine. It has now expanded to improve outcomes and reduce readmissions through remote monitoring and telehealth services. The program began with ten remote monitors for pulmonary conditions like COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder) and heart disease. It now has 100 monitors in place. Here’s how it works.

Each registered nurse working in the telemedicine system has 80 to 90 patients. Each patient files daily reports using a digital tablet in their home. Patients report blood pressure, respiration, weight, and oximetry each day. These biometrics are reported to the software platform that automatically alerts the nurse to any abnormal values for the patient. Staff will then intervene immediately to address the situation. Depending on the patient and the condition, they may schedule an appointment with a provider, educate the patient about medication dosage or adherence, or take other actions. The interventions are conducted by telephone or video visit. The results show that this telemedicine delivery system is working. According to Health Systems, it has helped to “reduce the 30-day readmission rates for heart failure patients to 4 percent, and 30-day readmissions for COPD patients is 2 percent*.”

Medicaid is beginning to come on board.

It’s been slow, but Medicaid is beginning to see the value of telemedicine and reimburse it. Given the older populations in rural communities and the density of Medicaid subscribers they represent, that’s a good thing. It is key to the implementation and success of telemedicine in those areas. Increasingly, states are passing laws that make a patient’s home an approved “originating site” for reimbursement for the use of telemedicine. That removes a major obstacle to physicians delivering care to patients at home and being reimbursed for it. So far, ten states specifically approve the patient’s home as an originating site for Medicaid- reimbursed telehealth programs. They are:

- Delaware

- Colorado

- Maryland

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Missouri

- New York

- Texas

- Washington

- Wyoming

In all, 49 states and Washington DC provide reimbursement for some form of live video in Medicaid fee-for-service.

Also, CMS has established its own “Rural Health Strategy“ to pay attention to rural patients’ needs. According to CMS, the strategy is designed to “provide a proactive and strategic focus on healthcare issues across rural America.” CMS says it wants to ensure that “nearly one in five individuals who live in these areas have access to care that meets their needs.” The goals of the program are to:

- Ensure access to high quality, affordable healthcare

- Advance telehealth

- Improve access through provider engagement and support

- Empower rural patients to make decisions about their healthcare

- Leverage partnerships to achieve these goals

The more that CMS recognizes needs in rural communities, the more telehealth may be supported, expanded, and reimbursed.

Government support for rural telemedicine

Other government agencies have lifted their collective heads to recognize the value, and power, of telemedicine in meeting the needs of patients across America. The chairman of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) recently announced that he has support to increase funding for the Universal Service Fund’s Rural Healthcare Program by $171 million a year. Chairman Ajit Pai said most FCC commissioners support the expansion of the funding cap from $400 to $571 million. “Telemedicine is vital in many communities that may not otherwise have access to high-quality health care. The Federal Communications Commission has an important role in promoting it.”

Veterans received a boost as well, with the passage of a bill that will improve healthcare delivery through telemedicine for veterans. The Veteran’s Administration(VA) announced that a new federal law had been passed to allow telehealth services to be delivered to veterans across state lines. This is an important advance in telemedicine. Previously, laws prohibited the delivery of telemedicine services across state lines except in particular, very narrow cases. Now, VA doctors, nurses, and other healthcare providers can use telehealth technology to deliver care to veterans. According to the VA, it can now be delivered “regardless of where in the United States the provider or veteran is located, including when care will occur across state lines or outside a VA facility.”

Consequently, that’s a win for veterans and telemedicine, whether it supports veterans living in rural or urban areas. It appears to be a significant step that begins to loosen the reins on telemedicine to do what it does best – provide health services across barriers to care.

Rural healthcare is more than the existence of one small hospital serving the people in a remote area. It is communities of real people with genuine healthcare needs. It is an aging rural population with chronic disease management needs that may not access care. The technology is available to make miles disappear. It can successfully deliver providers and health care into the living rooms of these people. To not do so is irresponsible.

Advanced practice provider and physician care can be expanded with the use of telemedicine. It can provide patients with consistent, cohesive care that can improve outcomes and improve wellness. It can deliver life-saving chronic disease management and improved medication adherence. As CMS, the FCC, and the VA embrace telemedicine, it behooves physicians and healthcare systems to do the same. We can now reach those who have struggled to access care. Let’s hurry up and do so.

*previous rates were not available for reporting